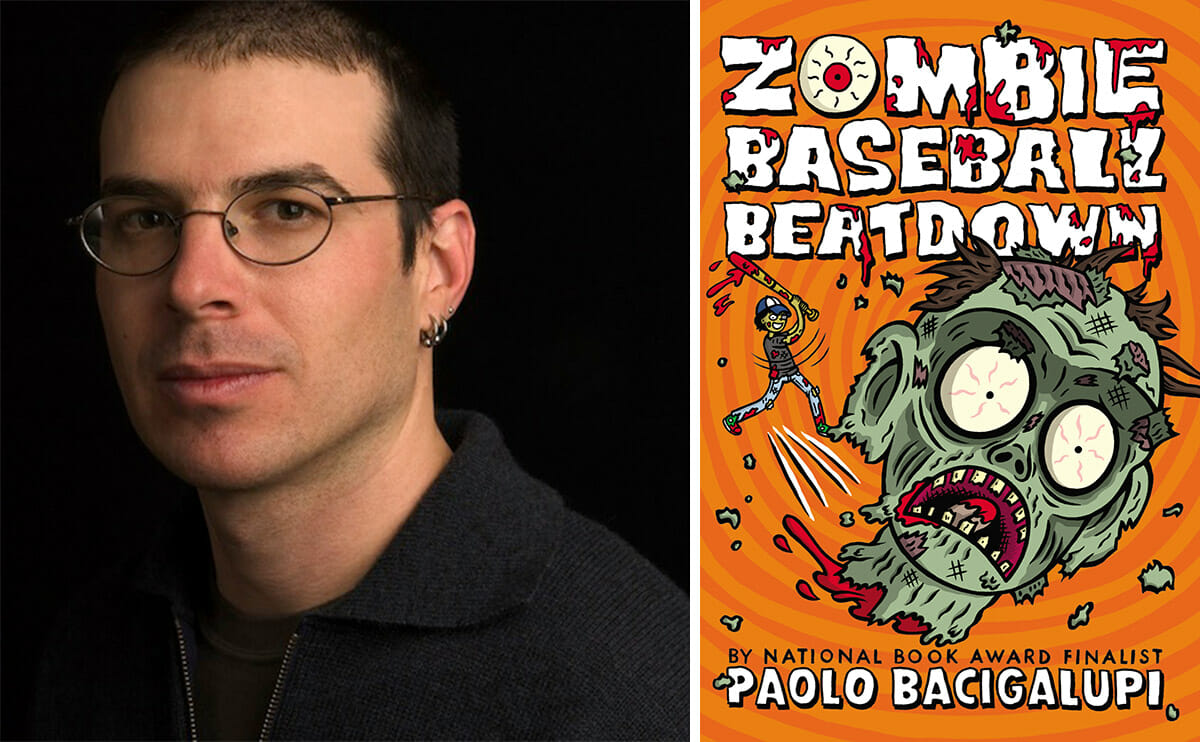

Why a Book About Zombies Could Get Kids to Eat Better

How a novel about bashing in zombie’s brains with a baseball bat carries message Michael Pollan would approve of.

Modern Farmer: The zombie apocalypse has started in so many ways – how did you come up with the idea of it coming from a cattle feedlot?

Paolo Bacigalupi: It felt like an awfully natural assumption, actually. There’s an accumulation of facts that keep coming out of our meat packing industry: mad cow disease and how industrial systems feed our cattle, how we give them protein, the amount of antibiotics that we pour into cattle.

It’s a space where it’s already dirty and infested and loaded with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. So when I was kicking around an idea on how to build this book, of course that’s where the next horrific disease is going to arise. Almost every detail that you pull out of a meat packing plant or a feedlot is just loaded with awesome details about how horrific that system is. If you’re writing a horror story, it’s made to order.

MF: These kids are running around with baseballs and bashing in brains of zombies, and yet a lot of what they get truly grossed out by is what they see as they get closer to the cattle feedlot.

Almost every detail that you pull out of a meat packing plant or a feedlot is just loaded with awesome details about just how horrific that system is. If you’re writing a horror story, it’s made to order.

PB: Right. The real horror is actually just the way business-as-usual looks. Every time you see an account coming out of how a meat packing plant looks, it is fairly horrifying. I remember reading an article about a journalist who had gone undercover as a USDA inspector at one point, and a cyst on a carcass exploded all over him. And you’re just like, “Whoa.”

The business-as-usual qualities are amazingly gross, and there’s a reason why the meat packing plants don’t want covert observers watching how they process meat at high speed. This is very un-photogenic; let’s not show this, shall we?

MF: At one point the meat packing company uses ag-gag to basically cover up the zombie infestation of the town.

PB: You know, the original reason that I wrote “Zombie Baseball Beatdown” was to get kids reading. I wanted to write a story for a kid who wanted to read about zombies. Then there was this odd cascade where I needed a reason for the zombie apocalypse to happen. I was already thinking about setting it in small town America. Oh! Local meat packing plant, I love it! A rural plant in a small town.

Once you’re inside the meat-packing plant, other ideas started really coming onto the page. The way workers are treated, the kinds of workers that meat packing plants hire, how they exploit their workers, things like that, which leads into questions about identity in America and immigration.

It also leads down these other paths, which are things like the ag-gag laws, how these big companies manage their public personas and how they work legislatively to keep their reputation squeaky clean. But all of that came into the book mostly by accident. You add in a meat packing plant, and suddenly you’re tripping down this long slippery slope of all these other strange things. It was kind of the gift that kept on giving.

MF: It sounds like you started wanting to write a zombie novel, and the food politics fed into it as you progressed along.

PB: Books can be a lot of different things all at the same time. That’s been my experience with almost all of the stuff that I’ve written, actually, where I’ll have certain ideas that I’m interested in working with. I’ll have certain goals or certain audiences that I want to talk to – and then there’s also my own values. All those things end up getting mixed up inside of a story.

It’s two things, really. I want my stories to be flat-out entertaining. I think that is the basic bar that every book owes its reader, is that it’s supposed to be an entertaining read. If you’re going to write about meat packing plants or GMO foods or politics or anything else, as soon as you go too far away from the idea that you owe your reader their entertainment, you get into that really didactic space where you see a lot of political literature. Even if you’re sympathetic, you say, “I’m bored” and put the book down.

So there’s the first part where you want to entertain. But other thing is I have to believe that what I’m writing matters on some level. That helps me push through to the end of the story; I have to believe that this story needs to be told, I have to feel like there’s some reason for this book to exist, that it actually serves some purpose in the world.

I mean, if I’m going to kill as many trees as I’m going to kill to have a book published, I want the ink on those dead trees to have some value. And so that’s another part, and that seems to be something that ends up infusing a great deal of my writing at this point, where I want it to be about big ideas and important topics that are worth cracking in and exploring.

MF: Food systems are something that you’ve been writing about for a long time. In your novel “The Windup Girl,” you create this dystopia based in a world where GM crops run amok.

PB: When I was writing “The Windup Girl,” I was really interested in the idea of what total corporate control of food would look like. You get an idea of what that looks like when Monsanto comes after farmers for planting a patented grain, the idea of food as intellectual property.

Corporations have to maximize profit – it’s in their nature, it’s not their fault, it’s what they do. They have quarterly yields and do a good job for their shareholders. And inside of that matrix, that’s going to define all of their behaviors.

As much as any major food corporation talks about feeding the world, what they’re saying is we feed our shareholders.

MF: In “The Windup Girl,” you play that out to an apocalyptic end. It’s a world where only GM crops can grow ”“ everything else is wiped out.

PB: Yeah. My idea was if I’m a company and wanted to develop total control, well, first of all there’s the terminator gene. Second of all, I want everybody to only be planting my food, so I’m going to release plagues that wipe out everything else that isn’t mine. Now everybody does need my food.

As much as any major food corporation talks about feeding the world, what they’re saying is we feed our shareholders.

A lot of science fiction does that. You look at some trend like the corporate control of food, and say, alright let’s turn the volume up to eleven on this. What does it look like if they control everything, if everyone is dependent on them?

And then you get to play in that world for a while, and give readers, ideally, a visceral experience of that. And when they read the newspaper, suddenly it’s been contextualized because they’ve seen the version that’s so horrific that a passing news story about Monsanto becomes relevant to them in a way that it wasn’t before.

MF: In your more recent short stories, you’ve moved away from GM crops to look at the implications of us living on a warmer earth.

PB: I’m really interested in where our prosperity comes from, and what undermines prosperity. What are we actually dependent on for that? We’re dependent on cheap oil for a lot of our prosperity. And we’re dependent on stable food supplies and stable water supplies.

Climate change is this interesting thing because we’re spending so much time in the United States in denial that it exists. And that’s amazing to me, because it’s like this collective decision to decide that data isn’t real. Data is now something that we believe or disbelieve. It’s this moment where we’ve lost track of realities, we seem to have lost the thread entirely. And then what does that mean?

That’s really the most fascinating thing to me about climate change. I was down in Texas during their drought a couple of years ago and Rick Perry was praying for rain. You have a viable political candidate running for president, and at the same time he’s praying for rain. This isn’t a national joke, this is a guy running on a platform that says that climate change doesn’t exist, but hey, you know, we’re in the middle of a drought, so let’s pray it away.

If I look at climate data, it says that your drought is going to get bigger and badder and more horrible over the coming years. Your only option, if you’re an engaged data-driven person, is not to pray for rain, but plan like that drought is coming for you big time.

Rick Perry praying for rain just felt like it encapsulated a moment. It was actually the moment where I decided that I was going to write “The Water Knife,” which is my next big novel. There was this moment where you just looked at that and you thought, “Wow, we are fucked.” We can’t even engage with this core idea that our world is changing around us.

MF: So that’s what “The Water Knife” is about?

PB: Sure. Little, Brown will love that I’m talking about my next adult book instead of my kid book. “The Water Knife” is set in the Southwest, and it’s all about a water war between Phoenix and Las Vegas. They’re fighting over dwindling supplies of the Colorado River. This is based on this understanding that we already know that Lake Powell is low, that Lake Mead is low, and that they’re only going to get lower.

It’s really a story about two cities looking at the future, and one of those cities deciding that it was going to pretend as though the future isn’t a big Mac truck coming to run them over, and the other one saying, “Wow, we’ve got to dodge somehow.” There are the ones who plan and anticipate, and the ones who live in denial. That’s the frame for the story.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Jake Swearingen, Modern Farmer

May 23, 2014

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.